Women working in agriculture in Egypt, Credit: Chrouq Ghonim.

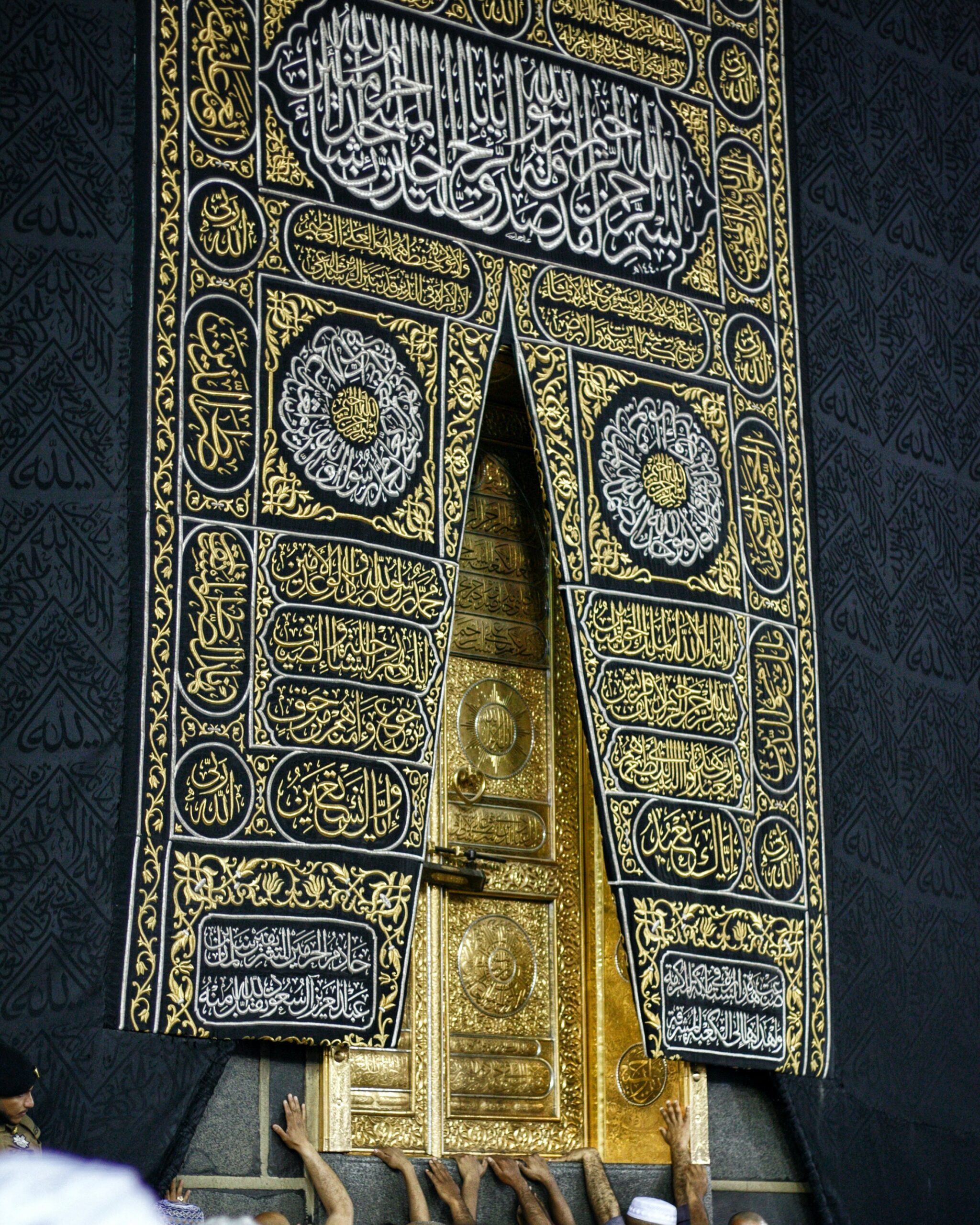

Accompanied by the women of the village, Nahamdo El-Shahat (55 years) walks for two hours a day from the village of Al-Dahsa, located in the Farshout Center in Qena Governorate, to neighboring villages to fill water buckets for her family to obtain safe drinking water.

According to Nahamdo, since the village’s founding a century ago, the women have been responsible for collecting and providing water. This is a profession that we inherited from our mothers and grandmothers a long time ago. The ladies of the village used to go out at dawn to find water.

The annual report of the Egyptian Water and Wastewater Regulatory Agency 2018 reported that Nahamdou is not alone in her situation, as one million and 181 thousand Egyptians cannot get clean drinking water.

Since she lost her eldest daughter five years ago while filling the water, Nahamdou, who complains of “varicose veins” and constant pain in her legs due to the long distances she travels, cannot declare her refusal to search daily for water, because there is no alternative for her in the family. Her daughter was struck by a car on the highway between the villages of Al-Dahsa and Al-Arki, and the driver escaped. Her other daughter and her husband were uprooted and relocated to Cairo searching for a better available job for the husband, whose farm had dried up as a result of the continued scarcity of irrigation water.

Data analysis of the Drinking Water Regulatory Authority’s annual reports reveals a five-fold increase in the number of Egyptians who are deprived of potable water between 2010 and 2018, as well as a nine-fold increase in the population served by a shift system, meaning that water only reaches them during specific hours each day in the same period.

A United Nations report claims that women and girls are responsible for getting water for their families and spend a great deal of time each day doing so. Rarely does a family’s demand for water from distant sources go unmet, although it is frequently contaminated.

Women and girls spend more than 40 billion hours a year searching for water, exclusively in Africa. These are the hours that were thrown away and could have been used to advance one’s career, education, health, family life, or social life.

Egypt is facing a severe water crisis as a result of a decline in the number of water resources available per person, which went from 2,526 cubic meters in 1947 to less than 700 cubic meters in 2013 to 500 cubic meters in 2021, which is less than the water poverty line estimated by the United Nations at 1,000 cubic meters per year per person.

Dr. Adel Motamad, a professor of environmental geography, claims that climate change is mostly the reason for Egypt’s water shortage due to the reduction and withholding of rainfall at a time when rain or the Nile River is the region’s primary source of freshwater.

Since the underground reserve is linked to the amount of rain precipitation, using groundwater and wells for drinking and irrigation until the point of depleting the available quantities of groundwater leads to an aggravation of the crisis rather than a solution as It is not renewed in light of the decline in the rain, as is the case in the Kharga and Dakhla oases in the Western Desert of Egypt. Another contributing factor to the water crisis is overpopulation, which results in a shortage of water that cannot satisfy everyone’s needs.

Water sources in Egypt vary, but the main and largest source is the Nile River with a fixed share between 2012 and 2019, which is 55.5 billion cubic meters annually and 69% of the total water resources in Egypt. Reusing sewage and industrial water comes next, accounting for 17% of all water usage and 13.6 billion cubic meters yearly. According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, there are more sources including groundwater and rain, but they only make up a minor portion of the total.

According to Dr. Heba Moftah, a professor of water resources at Al-Azhar University, although all residents of the affected areas are impacted by the effects of climate change, women and girls bear a disproportionate share of these costs, particularly in rural areas with limited access to basic services and facilities, where they are typically responsible for providing drinking water. This is especially true in societies where many male family members are at risk of dying out. This is a result of people migrating to other, less afflicted places searching for job opportunities. This is a result of migration in search of job opportunities in other, less affected areas.

Additionally, she believes that the issue is more apparent in rural and Bedouin civilizations where women take part in men’s agricultural and grazing tasks.

Women farmers and water shortage

Set Abuha Shehata, a woman farmer, used to earn 40 pounds per day for her work on agricultural lands, but after drought hit the villages of Fayoum Governorate, her wages were cut by half, and she often spends an entire season without work.

I’ve worked in agriculture for twenty years, says Set Abuha. Such years have never before occurred in my life. Farmers in the governorate abandoned their dried-up olive trees in favour of the metropolis in search of employment. Due to the areas’ desolation, we are no longer employed. Even the famed olive trees in the governorate have dried up for years, so we have no jobs and, if we have, the landowners control us and cut back on our daily income in response to their loss.

Image Credit: Chrouq Ghonim, Women collect agricultural crops in Egypt.

Fayoum’s lands have major salinization problems. According to a study by researcher Raafat Ali, Head of the Soil and Water Uses Department at the National Research Center, roughly 54.15 percent of the lands in the Fayoum Governorate are desertifying as a result of the soil’s sodium and salinity high levels. As well as for other reasons such as high temperatures, lack of water, and irrigation with the sewage water.

In some of his previous press statements, Shaker Abu Al-Maati, head of the meteorology department, confirmed that olive production decreased by about 80% during the harvest season last year as a result of climate change. The local olive harvest in 2020 totaled about 497 thousand tonnes, whereas the crop in 2021 has so far ranged between about 100 thousand tonnes.

The Middle East Institute for Studies asserts that given that more than 55% of agricultural workers are women and that this industry is known for its low and precarious income, the effects of climate change on agriculture in Egypt are likely to be significant. This will have an impact on the millions of Egyptian women who depend on it for their livelihood.

According to the report, climate change would exacerbate the poverty that millions of rural Egyptian women who work in agriculture currently experience.

According to Dr. Adel Motamad, social and material aspects as well as the psychological consequences of this group of women coincide significantly with the overall effects of climate change on female agricultural workers.

On the standard of living, the deficit appears in providing the income on which they depend to support themselves and their families. When climate change intensifies, particularly during periods of low rainfall and drought control, some women farmers are forced to migrate, leaving their homes in search of less harsh environmental conditions, which is accompanied by significant psychological effects because of the feelings of alienation.

Image Credit: Chrouq Ghonim Agricultural workers in Egypt collect crops in the early morning

The director of the Women’s Center for Guidance and Legal Awareness, Reda El-Danbouki, believes that early marriage and environmental migration are just two examples of how women and girls are exposed to different forms of inequality because of climate change. Additionally, it increases forms of equality and obstructs attempts to tackle issues affecting girls and women, such as early marriage to participate in social life.

He contends that the risks associated with climate change worsen gender disparities by posing risks to women’s health, increasing workloads at home and out, and higher mortality rates than those of men.

The stories of Nahamdou and Sit Aboha are just two of the various examples of Egyptian women who were obliged to work in the additional profession due to the water shortage crisis and climate change just because they were female.

This report was prepared within the MediaLab Environment Initiative, a project of the French Agency for Media Development (CFI).