[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

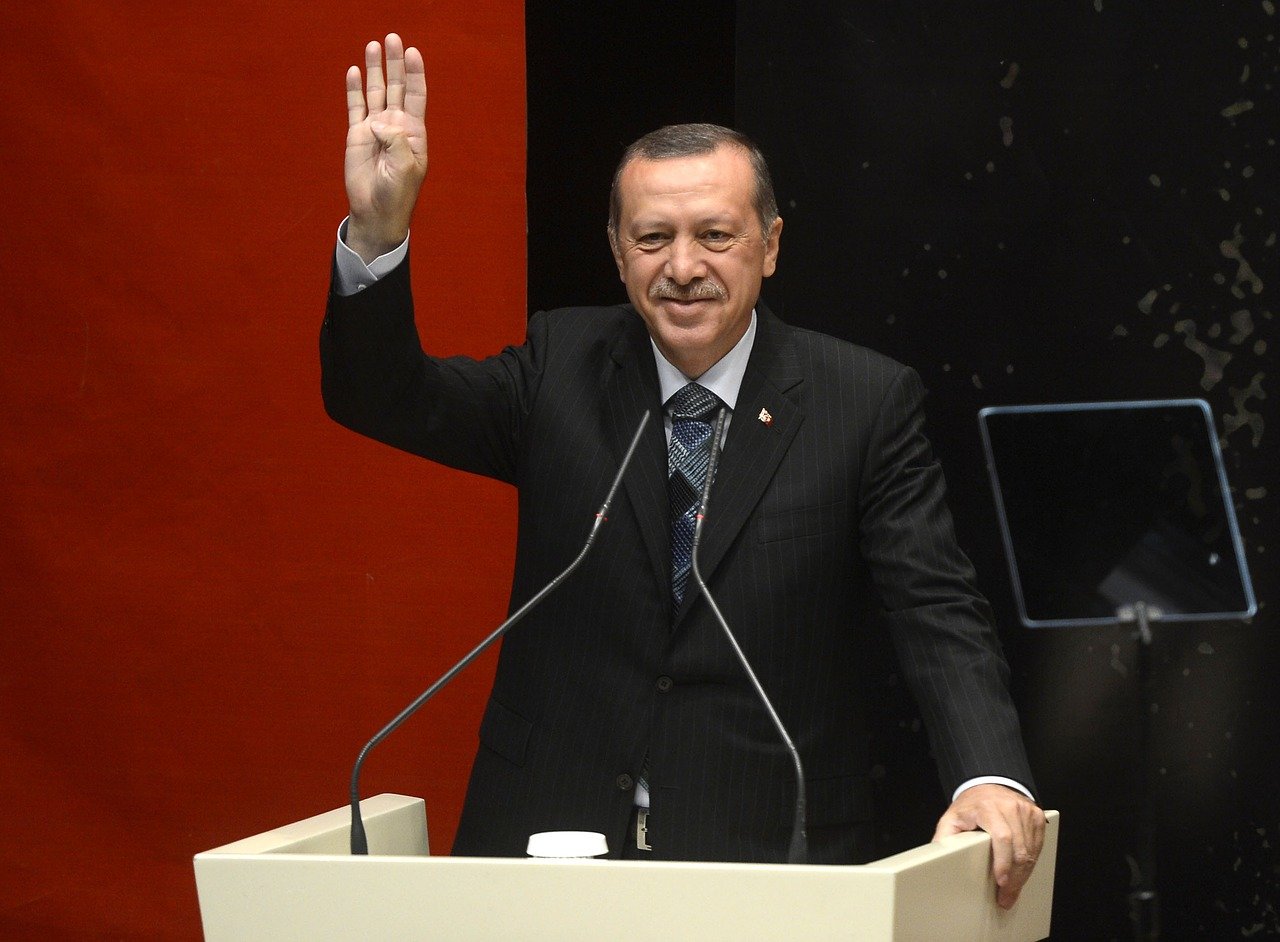

With an impending election planned for 2023 and a struggling economy, Turkey’s ambitious leader, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, finds himself at crossroads between his designs of aggrandizing Ankara’s profile to that of a leader of the Arab world, and the urgent need to salvage a dwindling economy through funding from the very powers whom he once sought to challenge.

Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), a conservative party with Islamist roots, have been in power since 2002. His era was marked by a fresh set of economic advancement and political reforms after a decade of instability. The country’s economy grew by 7.5 per cent on average annually until 2011. He followed a policy of “zero problems with neighbours,” and sought to proliferate Ankara’s influence in the region through trade ties, supporting democracy, and emphasizing its Islamic identity.

Erdogan’s leadership stature rose in the region after he openly stuck up in support of the Palestinian cause, emerged as a stable interlocutor between the Arabs and the West, and his narrative around building a neo-Ottoman empire. Many started equating him with Gamal Abdel Nasser, the unrivalled Egyptian president whose influence encompassed all of the Arab world during the 1950s and 1960s.

But by the second phase of his rule, Erdogan’s ruling party, the AKP, assumed a more authoritarian posture by controlling the media and military, while prosecuting and jailing critics and opponents. Using a referendum, he eliminated Turkey’s parliamentary system and installed a presidential setup.

Erdogan’s foreign policy too made a striking shift with a more assertive one focusing on expanding Turkey’s military and diplomatic footprint. This rejigging led Ankara to resort to a military offensive across surrounding countries including Azerbaijan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria; supply partners such as Ethiopia and Ukraine with drones; and build Islamic schools abroad.

In a bid to quash opposition led by Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant group that aims to establish a Kurdish state, Erdogan intervened in the Syrian civil war with the Turkish military occupying parts of northern Syria since 2016.

Ankara’s quest for energy resources has pushed it to strain its relationship with Greece over a conflicting territorial claim while deepening ties with Iran, irking Saudi Arabia. Its support of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt since the 2011 Arab Spring has upset Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Concerning the big powers, Erdogan’s approach has been that of setting foot in both the camps – the West led by the US and EU, and the Russo-China duo. On one hand, it appeared alongside NATO in Afghanistan, on the other side Turkey maintained deep energy relations with the Russians. The hope of joining the EU – Ankara’s biggest trade partner, led Erdogan to introduce numerous reforms.

However, his authoritarian reposting both in the Turkish internal affairs and its foreign policy exasperated his western allies, evident from the opposition by many EU members to induct Ankara into its league owing to Turkey’s undermining democracy, muzzling of the press, dissidents, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ+ community.

The refugee problem further strained the EU-Turkey ties. Although Ankara promised to block the passage of refugees through its territory if the EU increased its funding, Erdogan later issued a threat to “open the gates” in response to European criticism.

Washington and NATO have for long held Turkey’s geostrategic importance in high regard. Its territorial expanse across Asia and Europe renders Ankara a unique influence over Caucasus, Central Asia, the EU, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. The Turkish Straits are vital waterways between the Black and Aegean Seas. It hosts the U.S. and NATO military forces at several of its bases.

However, Ankara’s warming up with the American adversaries; namely Iran, Russia, and China, made Washington reconsider its strategic partnership with Turkey.

From the US alleging Turkey of circumventing its sanctions on Iran, to Washington siding with Kurdish groups in the Syrian war upsetting Erdogan, both countries have harboured multiple contentious issues. To add to this, Turkey went ahead and bought the Russian S-400 in 2019 much to Washington’s discontent. It is also deepening its ties with China, its largest import partner in 2021, joining Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, apart from allowing Chinese foreign investment. Experts say Erdogan’s proximity to China and Russia casts uncertainty on its future in NATO.

But the ongoing economic crisis seems to be overpowering Erdogan’s ambition of a Turkish Islamic leadership in the Arab world. With an inflation rate of 36 per cent and a national currency devaluation at 40 per cent, Ankara is seen seeking rapprochement with its traditional allies. His visit to UAE, earlier this year, to seek economic support and cooperation, substantiates his departure from the aggressive Erdogan doctrine. Notably, he had accused Abu Dhabi of attempting a coup to dethrone him. Its desperation to win back the West is evident from Ankara’s rallying behind Washington’s position against Russia over Ukraine.

The West too might not abandon Turkey yet. They need Ankara to be able to win the ongoing Ukraine war. Ankara is playing a pivotal role in supplying weapons to Kyiv. Its control of the Black Sea can help the West gain in its economic war against Russia. Most importantly, Europe could benefit from Erdogan’s effort to develop Turkey’s gas resources. For Ankara, the single most brownie point from reconciliation with the West will be getting its economy back on track.

However, even if all these rapprochement efforts transpired, Erdogan will make Turkey move significantly away from its prospect of leading the Arab world – a state of affairs that by no means places him anywhere close to the fiercely independent late Arab leader Abdel Nesser.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]