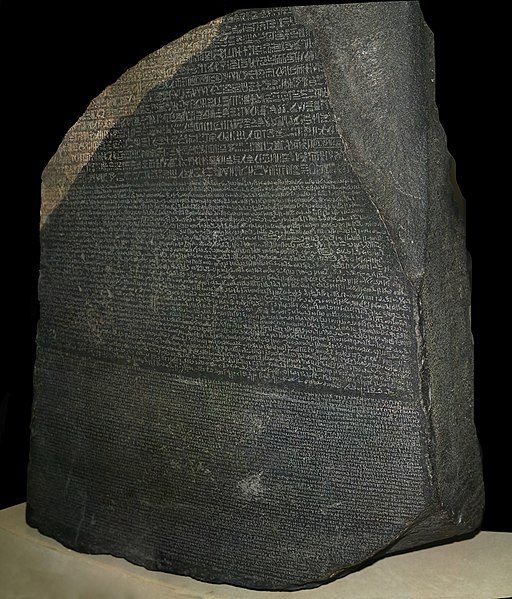

During the Napoleonic wars between Britain and France, the acquisition of the Rosetta Stone was tied up in imperial battles. In 1799, French scientists discovered the stone in the northern town of Rashid, which the French called Rosetta, after Napoleon Bonaparte’s military occupation of Egypt. In 1801, British forces seized over a dozen antiquities, including the stone, from French forces after they defeated them in Egypt.

The British Museum’s most popular exhibit, the Rosetta stone, has become the focus of controversy over who owns ancient artefacts, raising difficulties for museums across Europe and America.

An Egyptian obelisk dating back to the 12th century BCE was taken from Egypt to London by the British Army in 1801, and its hieroglyphic inscriptions became the key to unlocking the ancient Egyptian language.

Egypt’s biggest museum is celebrating the 200-year-old deciphering of hieroglyphics this year, and many Egyptians are now calling for the stone to be returned to their country.

The petition created by Hanna, which has 4,200 signatures, says that the stone was illegally seized and constitutes a “spoil of war.” A near identical petition created by Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former antiquities affairs minister, which has more than 100,000 signatures, agrees. According to Hawass, Egypt was not involved in the 1801 agreement.

The British Museum says this is incorrect. In a declaration, the Museum emphasises that the 1801 treaty includes the signature of an Egyptian representative. The Ottoman admiral who fought alongside the British against the French is mentioned. At the time of Napoleon’s invasion, the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul was nominally the ruler of Egypt.

Egypt’s government has not requested the Museum’s return, the Museum said. There are 28 identical copies of the same decree, and 21 of them remain in Egypt, it said.

The debate over the original stone copy’s unrivalled importance to Egyptology stems from its 2nd-century B.C. inscription of a settlement between the then-dominant Ptolemies and an Egyptian sect’s priests. It includes hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Ancient Greek texts.

In September, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned 16 artefacts to Egypt after a U.S. investigation found that they had been trafficked illegally. On Monday, the London-based Horniman Museum relinquished 72 objects, including 12 Benin Bronzes, to Nigeria after being requested to do so by its government.

Since el-Sissi’s administration has invested a substantial amount in antiquities, Egypt has been able to return thousands of internationally stolen artefacts to their homeland and open a new state-of-the-art museum that may house tens of thousands of objects. The Grand Egyptian Museum has been constructed for over a decade and has suffered repeated delays in opening.

In the year 2021, tourism to Egypt’s ancient monuments, including the pyramids of Giza and the towering statues at the Sudanese border, generated $13 billion in revenue.

Hanna asserts that preserving Egyptians’ right to their own history is of utmost importance. “How many Egyptians can visit London or New York?” she asks.

Image Credit: Hans Hillewaert Wikimedia Commons