Image Credit: Fer Ghanaa Ansari / Musawah

The clash between what we know as feminism and Islam has for decades centred around whether women have rights in Islam and how the interpretations of the Qur’an, view women second to men. Conversations around this topic usually flare up when issues surrounding the hijab or talaq (divorce) enter the news cycle. Often, these are reduced to debates about gender equality, where women are merely victims of a so-called oppressive religion.

This tense relationship between feminism and Islam has also resulted in the assumption that feminism can only triumph when religious discourse has been relegated to the private space. What is missing from these conversations though, is the scholarship of Muslim women working within Islamic law. Where are the women who studied Islamic law? Where are the alternative interpretations of the Qur’anic exegesis and Shari’ah that we don’t get to hear about? More importantly, how are Muslim women seeking to bring about change in Muslim family law?

The story of the term ‘Islamic feminism’ goes back to the 1990s as “a brand of feminist scholarship and activism associated with Islam and Muslims” says Iranian anthropologist Ziba Mir-Hosseini in her journal article Beyond ‘Islam’ vs ‘Feminism’. In this article, Mir-Husseini argues that both secular feminism and political Islam have been unable to “secure justice for women and have lost credibility and legitimacy.”

Perhaps the most important questions to ask then, are, whose Islam is it? Whose feminism is it? It is through this we begin to understand how the concept of “Islamic feminism” came about.

Patriarchal interpretations of family laws

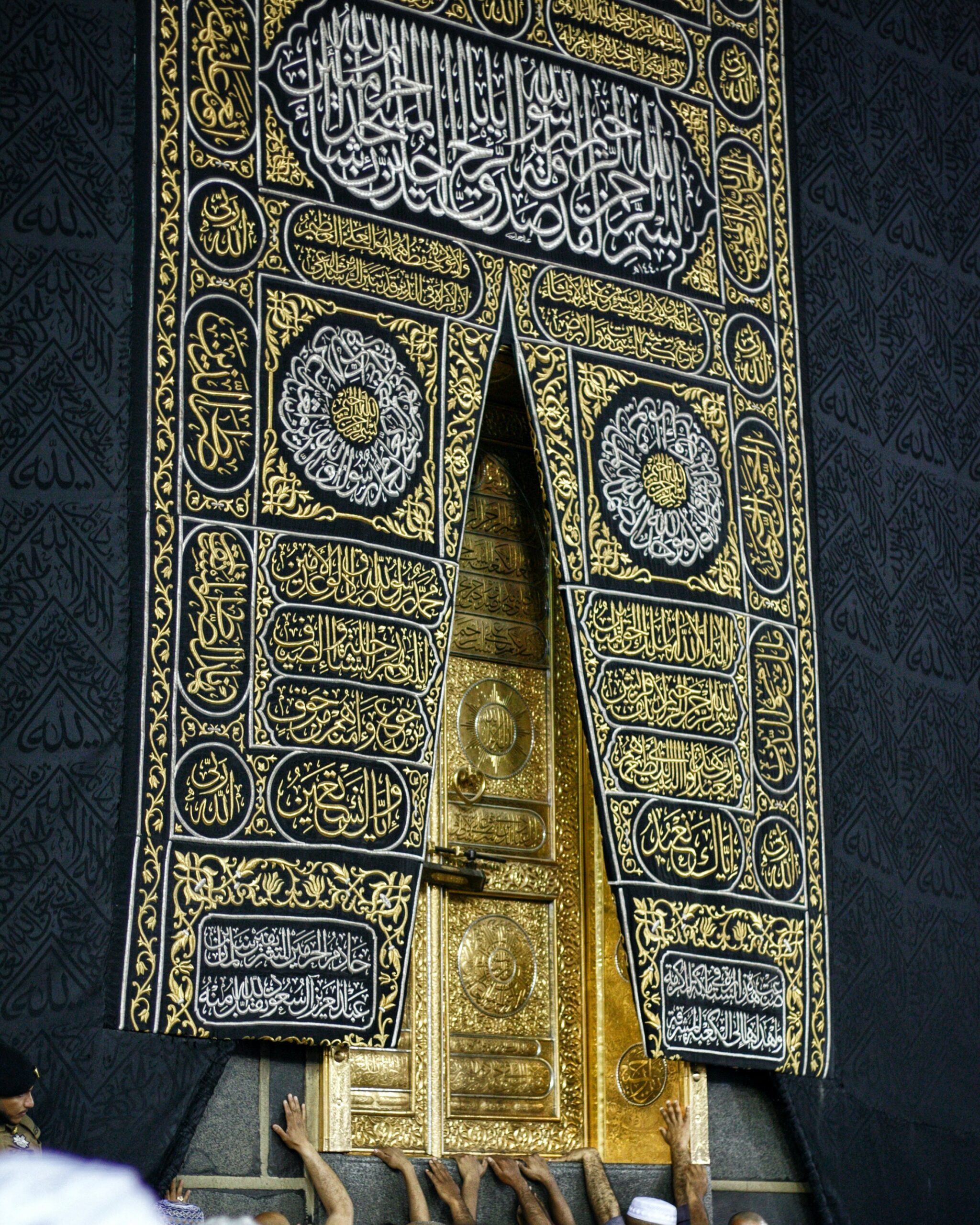

Advocates of the Islamic feminism movement seek to highlight the teachings of equality in the religion, and encourage a questioning of patriarchal interpretations of Islam by reinterpreting the Qu’ran and Hadith. Islamic feminists also set themselves apart from Islamists, who are advocates of political Islam – the notion that the Qur’an and Hadith mandate the laws of a nation. At the heart of the movement lies the belief that the rights given to Muslim women by God and the Prophet Muhammad have been denied to them by society.

Scholars like Mulki Al-Sharmani and Omaima Abou-Bakr have written on how Quranic verses with regards to divorce can be read through a feminist lens. For example, they explain in their chapter Islamic Feminist Tafsīr and Qurʾanic Ethics: Rereading Divorce Verses from the book Islamic Interpretive Tradition and Gender Justice that:

“…how Q. 2:232 admonishes men for attempting to ignore the woman’s wish to resume a previous marriage, or to contract a new marriage; it follows that the principle of recognizing women’s will and desire should be generalised throughout all related/similar steps or stages. This subtle point was set aside by jurists during the lawmaking process.”

Bridging the gap between Islamic law and feminism

How did these interpretations become patriarchal? Al-Sharmani and Abou-Bakr, along with Mir-Husseini, have all explained how the concept of “qiwamah” came to become the basis of traditional Islamic law. Qiwamah can be traced back to a verse in the Qur’an which says that men are the protectors of women. Mir-Hosseini in a webinar organised by the global organisation for equality and justice in the Muslim family, Musawah, went on to explain that marriage contracts often put women under the qiwamah of men: “Classical jurists define a marriage contract as a contract of exchange that puts women under the qiwamah of men. Here, qiwamah has an element of protection, and with protection always comes domination”.

Al-Sharmani and Abou-Bakr have also said that, “…in a survey of ten centuries of exegesis of Q. 4:34 – starting with the fourth/tenth century Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) – has shown that exegetes, through their accumulated layers of individual interpretations in the course of the patriarchal tradition, constructed qiwamah as a multidimensional patriarchal construct sanctioning male superiority and hierarchical spousal relations.”

Patriarchal interpretations have been deeply embedded in Muslim family laws, where a man provides for his wife in return for her submission and obedience. This underlying concept results in inequality in matters such as the right to divorce, financial security, choice and consent in marriage, sexual and reproductive health and rights, inheritance and nationality laws, and custody and guardianship.

Many Muslim women now want to reclaim what they believe are rights that Islam has guaranteed them, but society has prevented women from accessing them. Activists around the world have been advocating for just family laws, which have resulted in changes being made in some countries. For example, the Supreme Court of India in 2017 banned the triple talaq as a means of divorce, and declared it unconstitutional.

Making Fiqh rulings accessible to everyone

The path for Muslim feminists towards just and equal family laws has not been easy. In an interview with Ziba Mir-Hosseini, also the author of her upcoming book Journeys Toward Gender Equalities in Islam, she explained how tough it had been for her to even study the lives of women in Iran.

“I was studying people who emerged as Islamic feminists, elite journalists who didn’t see a contradiction between Islam and feminism. Many of them at the beginning of the Islamic revolution believed in political Islam. But by the end they realised they needed to stand for their rights, and they realised the Islam they wanted to stand for, was not the Islam that had come in [due to the Iranian revolution].”

However, when Mir-Hosseini left Iran, all the data she had been collecting was confiscated by authorities. All she had left were the interviews with certain ulemas, because she had been recording them for a women’s magazine.

Through Journeys, Mir-Hosseini says she wants to open this dialogue to the general public. For a layperson many Islamic legal concepts can be difficult to understand, which is why the book is written in a way that can be comprehended by anybody. For example, Journeys’ last chapter introduces Sedigheh Vasmaghi, an Iranian woman who has a doctorate in fiqh. Vasmaghi is the perfect messenger to explain Islamic theology and issues surrounding jurisprudence to the masses at large.

Many activists also view Islam and feminism as mutually exclusive, which often hinders dialogue. When talking about the clash between secular feminism and traditional Islamic scholarship, Mir-Hosseini said, “…not every aspect of Islam is feminist and not every kind of feminism is in line with Islam. Part of Islamic feminism is to produce knowledge from within, to bring women’s voices within the production of knowledge. Feminist scholarship in Islam is recovering the voices that weren’t recorded.”

A huge part of the Islamic feminist movement is to challenge patriarchal ethics that inform law. This has to happen, as Mir-Hosseini concluded, “also at a social level, not only at a knowledge-building level. For women to know they have rights in their religion empowers them.”