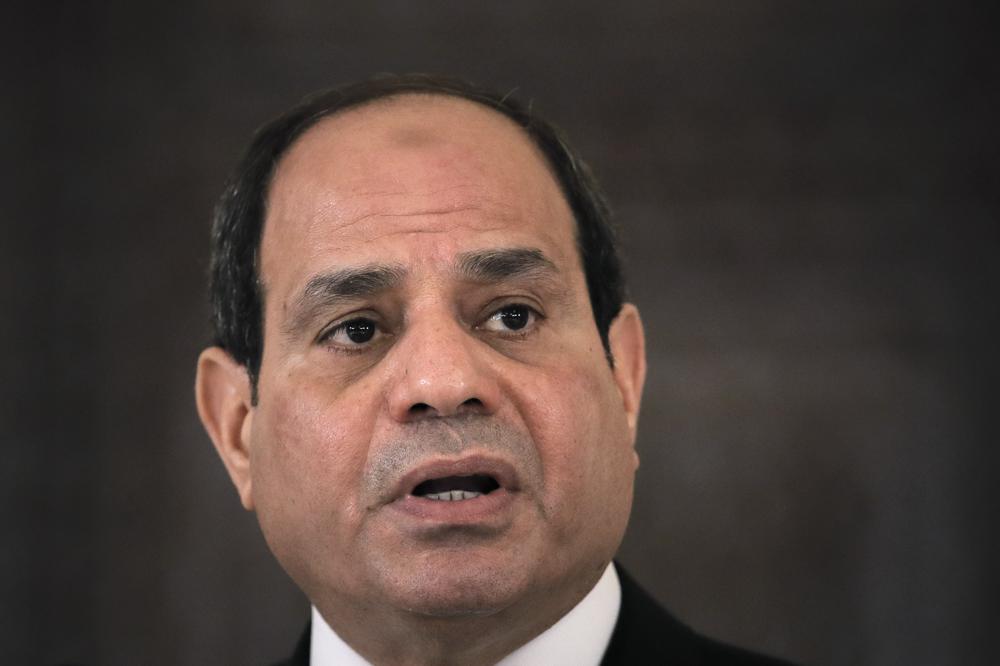

A few weeks ago, an elderly Egyptian mother appealed to President Al Sisi to have mercy upon her innocent son, jailed since 2009. She requested a Presidential pardon to release her son from prison. Her fear is that she will die before hugging her son again as his father had recently passed away.

Unjustly convicted in January 2010 without a fair trial, her son, Gerges Baromy, received a 15-year hard labor prison sentence. Held in custody for a year awaiting trial, Baromy, a bread vendor, was an innocent victim of sectarian violence and the unjust courts. During his incarceration, his family begged for mercy many times; it was denied four times. As tradition allows, requests are presented to the Egyptian president during the Islamic Feast of Sacrifice (Al Adha) when forgiveness is offered to well-behaved prisoners.

A Coptic scapegoat

Baromy was a bystander in the wrong place at the wrong time becoming the Christian scapegoat in an unverified rape narrative that allegedly took place in the daylight hours; no crime was proven. No facts were presented in the court except for an official medical report, which stated that Baromy was sexually impotent, rendering the accusation false. The young Muslim girl was never medically examined nor made a statement. Despite all this, Baromy was found guilty of rape.

Long before the verdict, rumor of Baromy’s guilt spread through the villages and sparked firebombing of Coptic homes and shops for five consecutive days forcing Baromy’s family to be displaced and lose their home. There was an immediate, unappealable Bedouin Court decision that permanently handed over Baromy family property to Muslim marauders and forbid the family to return to their village.

While Baromy was jailed without bail, Hamman al-Kamouni opened fire on a Naga Hammadi church killing one police guard and six Christians leaving the Coptic Christmas Eve service. Al-Kamouni said he was avenging the honor of the raped Muslim girl.

Baromy’s trial was seething with tension as the terrified defense attorney stood inside the courtroom while outside Islamic radicals surrounded the building. He managed to present the forensic report confirming Baromy’s sexual disability. Under intense pressure from vigilante forces, he was unable to complete his arguments, and nothing was presented by the prosecutor. Making matters worse, Baromy’s lawyers were now handling the high-profile al-Karmouni revenge case for the innocent murder victims, which distracted their energies away from the Baromy matter.

Baromy’s case became secondary for his lawyers who were more focused on publicity and legal victory in the Naga Hammadi martyrs’ case. Baromy became a victim of circumstance for a second time due to his lack of defense. Furthermore, upon his mother’s request for a pardon, his lawyers neglected to advise her that rape cases are an exclusion from presidential forgiveness.

The zeitgeist of Egypt was revolution. There were uprisings in the streets against President Mubarak. A not-guilty verdict for a Christian male accused of raping a Muslim girl was risking retaliation and street justice. In March of 2011, Baromy was declared guilty, and his legal right of appeal was denied.

The verdict had far-reaching consequences. The political insurrection in the streets used Baromy’s “victimhood” and “guilt” to fuel both sides of the religious skirmishes taking place. Coptic organizations, Egyptian human rights organizations, the anti-Mubarak revolutionary April Six movement, and socialists sided with Baromy, using the issue to pour into the streets and fuel anti-Mubarak protests.

Baromy’s village of Farshout returned to sectarian calm. State police were sent in and national security tightened everywhere to avoid any political spark that might ignite this volatile moment. No doubt Baromy was dealt a grave injustice as well as his mother who will now wait for 2025 for “injustice” to be served in full.

Image Credit: AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda, File