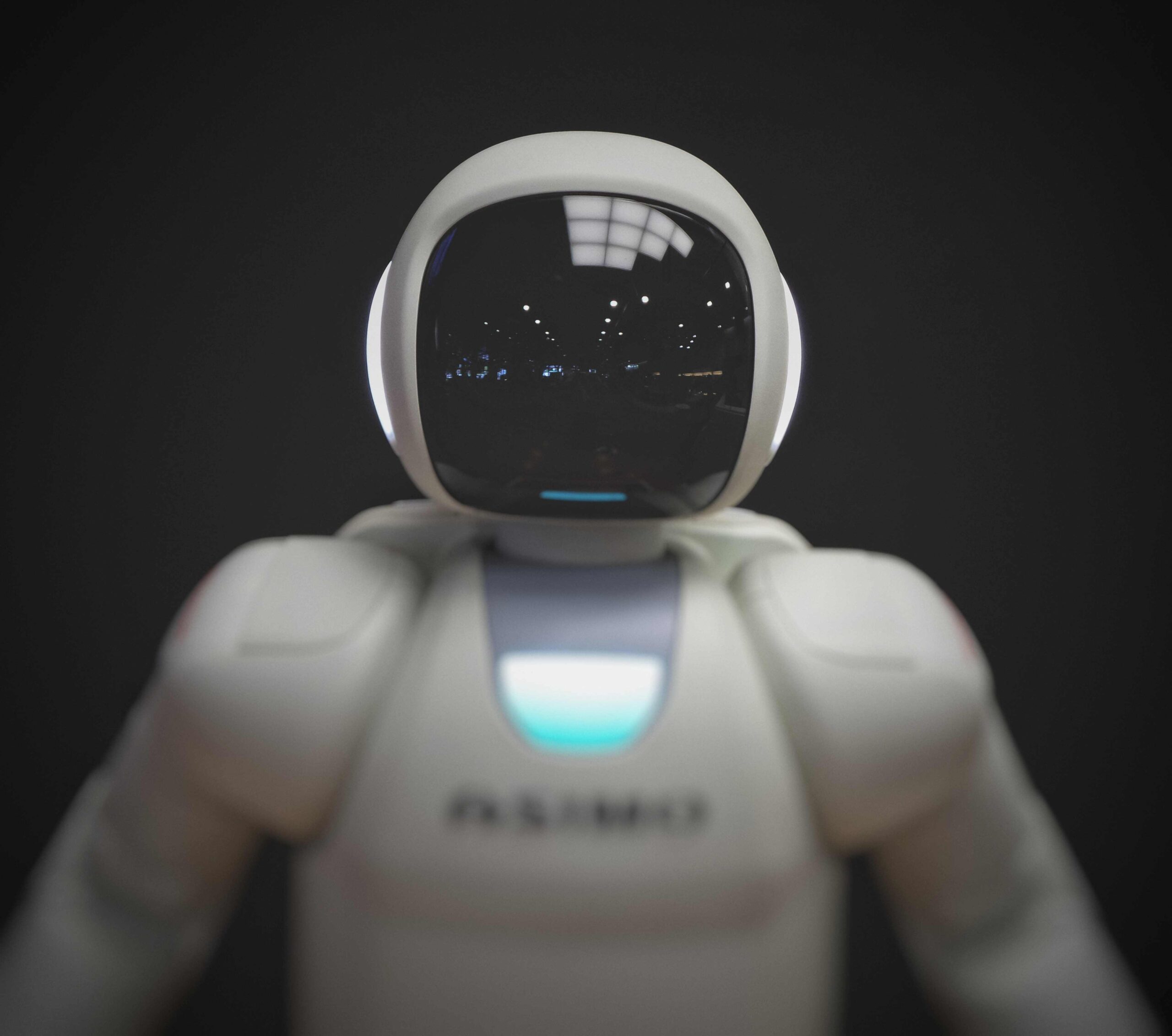

The most interesting idea about posthumanism is not just its connection to artificial intelligence and genetics or its philosophical and sociocultural ongoing debates, but its determined attempt to deconstruct the human; how the human is being constructed separately from the Other. If we do not address the current rooted dualistic mindset that constitutes hierarchical socio-political construction, therefore new forms of dualism will appear: posthumans, transhumans, and robots probably will be perceived as the new Other. If there is an overall interpretation of posthuman thinking, it is that the human is not fixed, yet always enmeshed with the nonhuman world in a web of complex, mobile, and reciprocal spaces of matter and changeable meanings. In the light of this proto-ecological mindset, the boundaries between humans and nonhumans are not merely changing, but also becoming accessible.

In the age of techno-humanism, posthumanism would mean nothing but the incompleteness of human beings and questions their exceptionalism. Since agency and subjectivity are not the attributes of only human beings, the most transparent manifestation of posthumanism locates it against the exploitation of women, animals, and the natural world. It demonstrates the fragility of the human, and considers the distinction between humans and nonhumans as boundless, and the perception of the posthuman subject as product of multiplicity and collectivity.

No matter how promising or pernicious it might appear, our future in its association with technology seems quite controversial and partly filled with concerns. Humans have always sought progress and attempted to use technology for their own sake. With that in mind, posthumans will most probably perceive the old and mediocre humans as the new Other. Lowly, secondary, and even savage, they fit only for subjugation and persecution. Perhaps part of the answer could be located in the different perspectives that transhumanists and bioconservatives have in regard to posthuman dignity.

This suggests that if posthumanism prevails, environmental humanism will be forced to consider self-representation as solely transitional and also relinquish its dependency on narratives of collapse and their sense of impending ending. The possibility of having posthumans in the future has procured considerable ethical and philosophical attention. With the emergence of transhumanism, the posthuman future is seen as a positive progress or as the mere way to evade the annihilation of intelligent life.

In this sense, it seems to be that there are many ways to distinguish between the two terms ‘posthuman’ and ‘transhuman’. The term ‘posthuman’ implicates individuals that are descendants of human beings but are no longer human, while ‘transhuman’ indicates individuals who possess abilities beyond human nature, yet a transhuman might still be regarded as human. To be true, the argument here demonstrates that we all should be in favor of a posthuman future, because it is good for human beings and for their well-beings, yet it turned out to be problematic. This vision reflects an utterly dynamic world, a world whose ontological understanding is performed rather than given, a world in which interlacing with the Other is the sole dynamic purpose of being. In this hybrid space, different forms of agency and materiality interact with each other, and humans are part of this intricate web of ontology, signification, and phenomena.

This dichotomy exacerbates and elaborates the need of posthuman dignity. Bioconservatives deny posthuman dignity, while transhumanists believe that human and posthuman dignity are interrelated. By guarding the transhumanist view, our future seems to be heading towards a more inclusive and dignified human ethics, one that will embrace future technologically modified people as well as humans of the contemporary kind.

An opposite aspect of importance is that posthumans would most likely have brains that cannot stand alone, but rather connected directly to a network. Also, it has become problematic to argue that we should encourage development towards a post-human condition, just because it is positive for individuals and beneficial in general. The more posthumans are, the more difficult it becomes to assess and to compare their individual well-being to our current status.

George Orwell says that if you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever. While the posthuman world promises us more human progress, serious aspects of human liberty unearth themselves as to question the moral edge and the untamed extent of technology. It must be said with vividity and intrepidity: Technology will either free us or enslave us.

Image Credit: Possessed Photography on Unsplash